Travis Beck: Tough Love for Native Planters and Permaculturalists

Native Plants and Permaculture. Two compelling philosophies that have created exciting tides in horticulture. Tides might be polite; maybe trends may be more accurate. As with any trend, once we all start to buy in, its easy to lose the scent of the original rabbit we were chasing. Elitism and smugness always seem to creep in and foul the waters.

Last summer I had the great fortune to meet big gun rock star landscape architect Travis Beck. Currently the Director of Horticulture at Mt. Cuba Center, Travis was also the project manager for the new native plant garden at NYBG. Halfway through his book Principles of Ecological Landscape Design I knew that I had to get him on NativeBergen.To visit a professional garden is always a treat but how often do you get to pick the brain of a blue-chip garden professional? I felt it only fitting to ask Travis, this Formula 1 level plant professional for a few of challenges: two for the permaculturalists and two for the native planters.

Dear native plant enthusiasts, please stop saying native plants are easier to grow because they are perfectly suited to their environment.

If easy-to-grow were the criterion, we should have Japanese knotweed, tree of heaven, and Norway maple everywhere. Wait, we do! And part of the reason we do is that we have altered the environments that best suit many of our native plants. In most places where we get to choose what to plant, the native soil is long gone, drainage patterns are different, sulfur dioxide and nitrogen rain down from the air—whatís a poor native plant to do? What we mean to say is that native plants are adapted to their local climate, which makes them more likely to survive when it gets cold or dry than fussy garden plants like fuschias or demanding bluegrass lawns. Native plants are, of course, diverse and grow in many different places and conditions. With a little research, we can find a native plant for that rain garden, or green roof, or highway median. But it may not be common in the trade. And that may be because it doesnít propagate easily, or grow quickly enough to make anyone any money, or look any good for longer than a few weeks. There are many great reasons to plant native plants, but working with natives is not inherently easy, and itís not automatically more sustainable.

Also, how is it that everyone who goes down the native plant rabbit hole pops up in love with some oddball group of plants?

Shale barren endemics, bog plants, swamp pink, Shortia. The rarer the better. Conservation value and collectors value go hand in hand. So are we saving biodiversity, or just showing off our membership in the class of connoisseurs? I say, donít forget the common species! It would be a crime to let the rarities disappear, but we could save disconnected populations of all the unusual species in the country and still have a lousy environment. We need more workhorses. More beach grass knitting into our dunes. More oaks pushing up in second-growth forests and peopleís yards, becoming entire ecosystems in their own right. More milkweeds spilling forth their downy seeds and hosting monarchs as they move from south to north. And if we succeed at that, there might just be more room for some of the oddballs too.

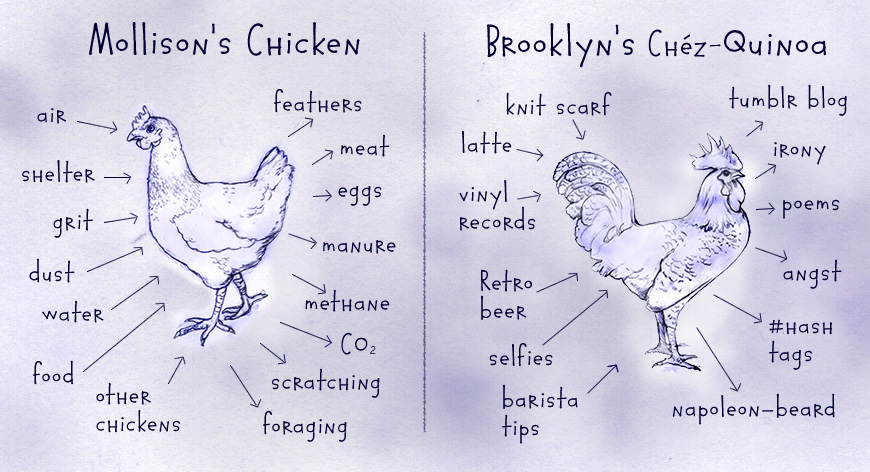

Dear permies, bring back the chicken! Not the ones in back of every fifth brownstone in Brooklyn.

Iím talking about the one that Bill Mollison used to illustrate an approach to permaculture design. The one that has needs like shelter and grit, behaviors like scratching and foraging, and products like eggs and manure. The one that, Mollison suggests, can be placed in beneficial relationship with the other elements of a system or a site. The one that shows that permaculture is a design methodology, not just a toolbox. Having chickens doesnít make one a practicing permaculturist, nor having a herb spiral or a hardy kiwi or a hugel. Practicing permaculture is employing a design art that maximizes beneficial relationships.

If that is the case, maybe permaculture doesnít have to look like permaculture as weíve grown used to seeing it.

Maybe we could get past the newspaper sticking out of the edges of our sheet mulch, the upcycled vegetable oil drum rain barrel, the shoestring budget suburban homestead warren of paths through an immature food forest. And enough with the comfrey! If permaculture is ever to become the world-shaking movement it deserves to be, it has to get out of the alternative lifestyle ghetto. Billions of dollars are being spent these days on sustainability, on local food, on green building. How many of these dollars are going to permaculture projects, and how much of the conversation is permaculture influencing? Canít we set aside the trappings and show how broadly relevant the principles truly are?

So there it is, four to grow on for growing season number two-thousand fourteen:

- Its not necessarily easy to grow native plants

- Native planters: Focus on the workhorses; not the show-ponies

- Permaculture is a holistic practice; not an accumulation of agro-hipster accessories.

- Permaculture is valuable and viable; with a little decorum it will persuade everyone; not just the counter-culture.

In books, on websites, in evening-meetings upstairs at REI: we can get very snug and smug in our horticulture philosophies. Its another thing entirely to have to create gardens that stand up to the most rigorous public scrutiny —and sometimes year ’round at that. I’m grateful for Travis Beck’s honest insight even if it stings a little. It was an honor to have even a little advice from a real garden heavy. It would be stupid to waste time asking him questions like: “Do you like piÒa coladas?” So if your feathers are ruffled… I think Mollison’s chicken would be cool with that. So is NativeBergen.

A very special thanks to Travis Beck for his keen insight and for being patient with me during a very difficult personal time. If you are in the Delaware area be sure to visit Mt. Cuba Center. Thanks also to Garrett Bibb in Marietta Georgia for the illustrations. April 27, 2014Posted in IDEAS, PEOPLETags: native plants, permaculture, Travis Beck 2 Comments

2 Comments

I'm glad to see a reputable gardener offering some criticism to the permaculturalists, but I feel that he wasn't quite hard enough on them. I met a young man who was giving a permacultural talk at a local library. He was a massage therapist who undertook a long-distance summer learning course with an instructor from Australia. He had no prior background in gardening, agriculture, or sustainable ecology. The young man decided to quit his job as a massage therapist and was in the process of starting a business. It appeared that he spent more money on his business cards than his permacultural education. Anyway, the young man decided to go on the whole chicken spiel. He reiterated all the "by-products" and "processes" of a chicken feed to him by his permaculture course. Essentially, he said that he was going to start growing chickens in the suburbs of Detroit for their by-products(manure/fertilizer). But this is where things get rather ridiculous, and quickly at that. The young man mentions that he is a vegetarian. This means that he will not be utilizing the meat for personal consumption, and will likely shy away from butchering the meat to sell to others. Essentially, the young man wants to raise chickens for their manure to use as fertilizer. He wants a sh** farm. And by misinterpreting the design principals of permaculture, this young man thinks a sh** farm in the suburbs is a sustainable, closed-loop cycle. As far as fertilizer goes, he could product friable compost with the vegetal by-products of his gardens. He could also produce compost tea. Yet, because chicken tractors are now all the rage, the young man desires to utilize a project unsuited to both his lifestyle and his environment in which he live, which is inherently unsustainable. One of the factors to consider in permacultural design is whether or not a particular project is appropriate in a given context. If the project does not fit the circumstance, as a methane digester on a property which does not produce enough methane to warrant having one(another permacultural favorite), it produces a net loss of time, energy, resources, and space. Few of these younger students are thinking on such levels. Que Bueno July 13, 2014 at 11:16 am

Since my collaboration with Mr. Beck, there are two things I've learned:

1. I need to learn so much more! I need to study books. I need to talk to experts. I need to observe the natural environment. Zealousness mixed with ignorance has gotten us into so much damn trouble.

2. Our green landscapes are hyper, super, mega local. What works at the end of my street may not work on the other side of my town. Pick whichever garden manifesto you like! —your local bugs, animals, weeds, soil and pollution will laugh in its face.

So perhaps the criticism with this young man's permaculture is actions and beliefs without knowledge and context. I'm learning the same criticism can be leveled at native plant fervor. Thank you so much for your comments. óNativeBergen July 13, 2014 at 11:07 pm